Designing homes that connect to nature is a big part of what architect Camille Jobe does, and California is one of her favorite spots to do it. “It’s a choice place to practice because you can do all of the things to open up the house,” she says. More often than not, though, Jobe’s commissions are closer to Austin, Texas, where her firm, Jobe Corral Architects, is based. And even with the heat and humidity of Texas, she knows how to connect a house to nature and keep things relatively comfortable.

The architect points to a home she designed in Texas Hill Country, where a cross gable structure bisects the main structure. “It’s entirely glass in those gables at both ends, with big doors that open up,” she says. The design follows an approach she often employs with multiple access points to the outdoors, whether by way of doors that open wide or with what she calls “morning porches” and “evening porches,” or “summer porches” and “winter porches.” “Even when it’s the hottest in Texas,” she says, “there are places where you can catch a breeze and it’s bearable all year long.”

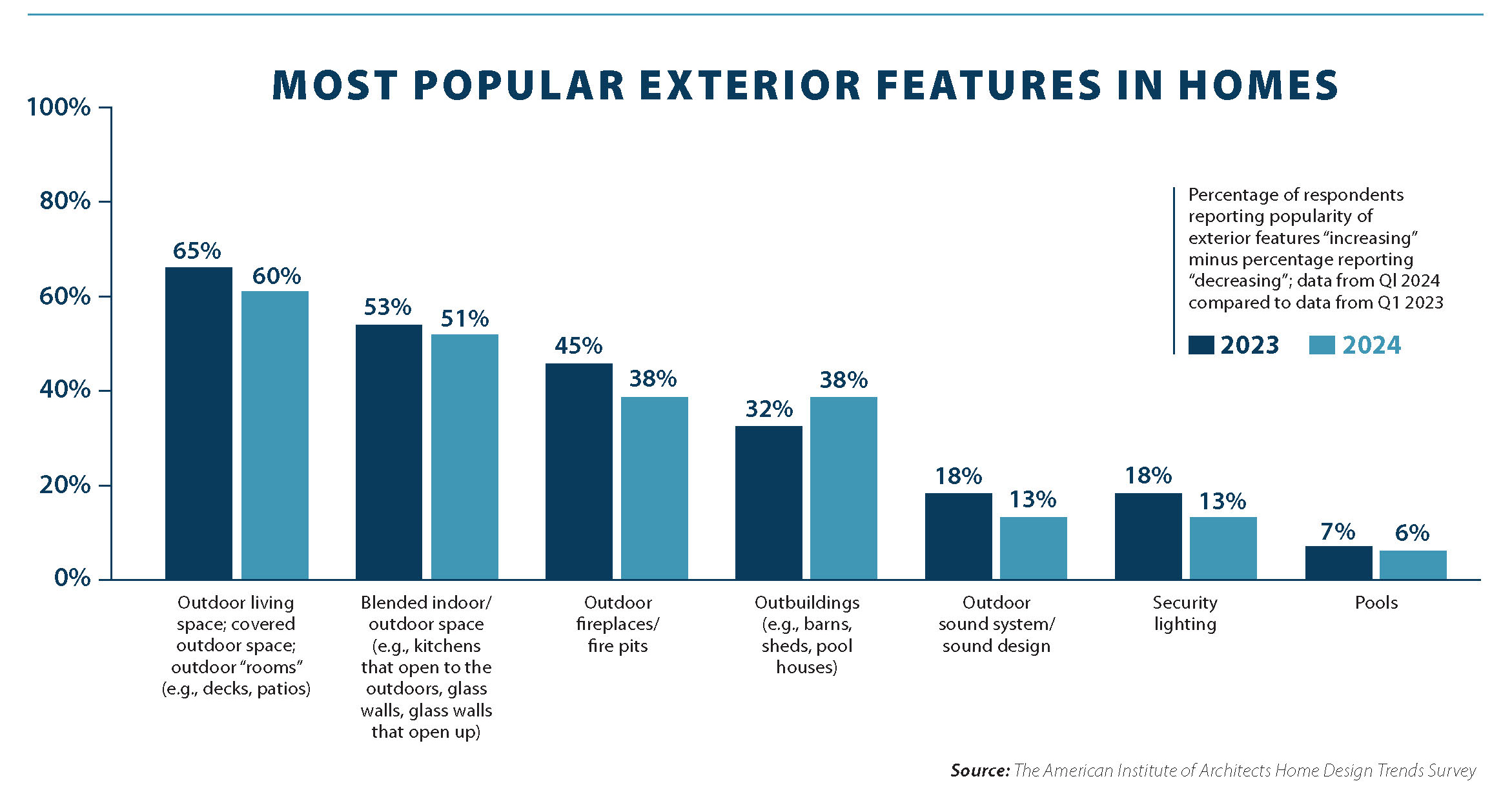

Her clients’ requests are in line with those of most architects’ clients, according to the 2024 American Institute of Architects Home Design Trends Survey. “Outdoor living spaces and blended indoor/outdoor spaces continue to top the list of exterior features in homes,” the survey notes, with 60 percent of respondents reporting popularity for outdoor living spaces such as decks and patios, and 51 percent reporting popularity for features such as glass walls that open up.

A Fundamental of Modernism

The idea is nothing new for architect John Klopf, whose San Francisco firm, Klopf Architecture, specializes in mid-century modern renovations — and new homes inspired by the style — that open wide to the outdoors. But his thinking goes back to a time way before modernism. “It’s an age-old approach to connecting people to nature through the architecture,” Klopf says. “And I say it’s an age-old approach because it has to do with bringing in daylight to wash surfaces and make interior spaces feel bigger and brighter than they are. It has to do with having open views out to courtyards and natural views, where applicable. I like to use the Japanese term ‘borrowed landscape,’ where a courtyard or a view is an extension of the room.”

Still, the modernists were on to something in their endeavor to blur the lines between indoors and out, something Klopf’s clients value now more than ever. “A lot of times [clients] will say to me, ‘I really like the idea of the indoor/outdoor flow in these homes,’” Klopf says. “That’s great because, to me, that’s the fundamental of the style. The architects pushed and pushed. If they were designing now, they would be using these multipanel sliders and folding wall systems.”

Plenty of opportunities also exist for homes where strong indoor/outdoor connections were never part of the original architectural intent. Jobe’s firm, for example, has renovated several smaller 1940s-era concrete block-and-stucco homes — many with small additions that connect to the outdoors — in an Austin neighborhood valued for its character and where teardowns are discouraged.

After putting the first couple of projects on home tours, Jobe recalls, “Everyone who went through there said, ‘I had no idea you could do this with these little houses and have such great connections to the outdoors.’ That just wasn’t happening here in the ’40s.” Similar praise has poured in regarding the renovation of her own house in the same neighborhood. “I cannot tell you how many people think it’s twice as big as it is because we have figured out how to make those indoor/outdoor connections a little bit better,” she says. In most cases, Jobe specifies folding doors or pocketed sliders. “Thinking back 20 years ago or so, you had very few options for having nice big openings,” she says. “And now, depending on your price point, you can make doors disappear completely.”

Innovating New Possibilities

Thanks to innovations in oversized doors, firms like Christopher Strom Architects, based in Minneapolis, now often specify them in their region, where winters can be harsh. “People can picture those steel warehouse windows with very, very thin frames,” Stom says. “They don’t perform that well in the wintertime, but manufacturers have learned to do those very thin profiles with aluminum and wood.” Strom often specifies multi-slide doors. “You don’t need much of a threshold, so when all of those doors are out of the way, it leaves you with this very minimal transition,” he says. “So, you can have the same level inside and outside, and the flooring material kind of skates right through it. When the door is open, it just feels fantastic.”

Klopf appreciates the innovations, too, which address problems he has seen in some mid-century modern homes with old flush-to-the-floor doors, including rot and water intrusion. “Now there are great options available for thresholds so that your door is flush with your exterior patio level,” he says.

Architects now have door choices that are bigger than ever — and that practically disappear — from JELD-WEN and LaCantina. (Jobe and Klopf are among them; both have specified large door systems from LaCantina in their projects.) Scott Alden, Architectural Consultant at JELD-WEN, uses a multi-slide glass door system as an example of how far an architect can go. “It’s not unheard of to have 60-square-foot panels that are 6 feet wide, 10 feet tall,” he says. “You can go with eight of those panels — four going in one direction, four in the other. That’s 48 feet of wall, 10 feet tall. This is just one configuration among many that multi-slide or folding systems offer. It gives you a huge view and makes the separation between indoors and outdoors invisible.”

For More Details

See how patio doors — including the largest sizes from JELD-WEN and LaCantina — can blur the lines between indoors and out in the projects you design. Find inspiration in our patio doors gallery.

Find a JELD-WEN dealer or retail location near you here.

Comments are closed.