Visiting the ancient temples of Kyoto, Japan, early in his career, architect John Klopf found inspiration in the idea of biophilia that would factor into nearly all of his designs moving forward. “Seeing Japanese temples that had been around for hundreds if not a thousand years — and seeing how outdoor spaces are used as extensions of rooms — I realized how much people loved the idea and how it never goes out of style,” he says. “You feel calm, rested, and less stressed in natural environments.”

The restorative power of nature has been widely discussed for decades, but the topic has found more prominence in recent years, particularly in commercial architecture and design. The International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health reported that “biophilic elements such as plants, water, natural light, and visual representations of nature … in the workplace have been associated with benefits for well-being, mental health, productivity, and worker performance.” And “Why Biophilic Design Is Crucial in the Workplace and Beyond,” published by Gensler, noted that “the relationship between humans and their environment is a crucial factor in how they perform and connect with others.”

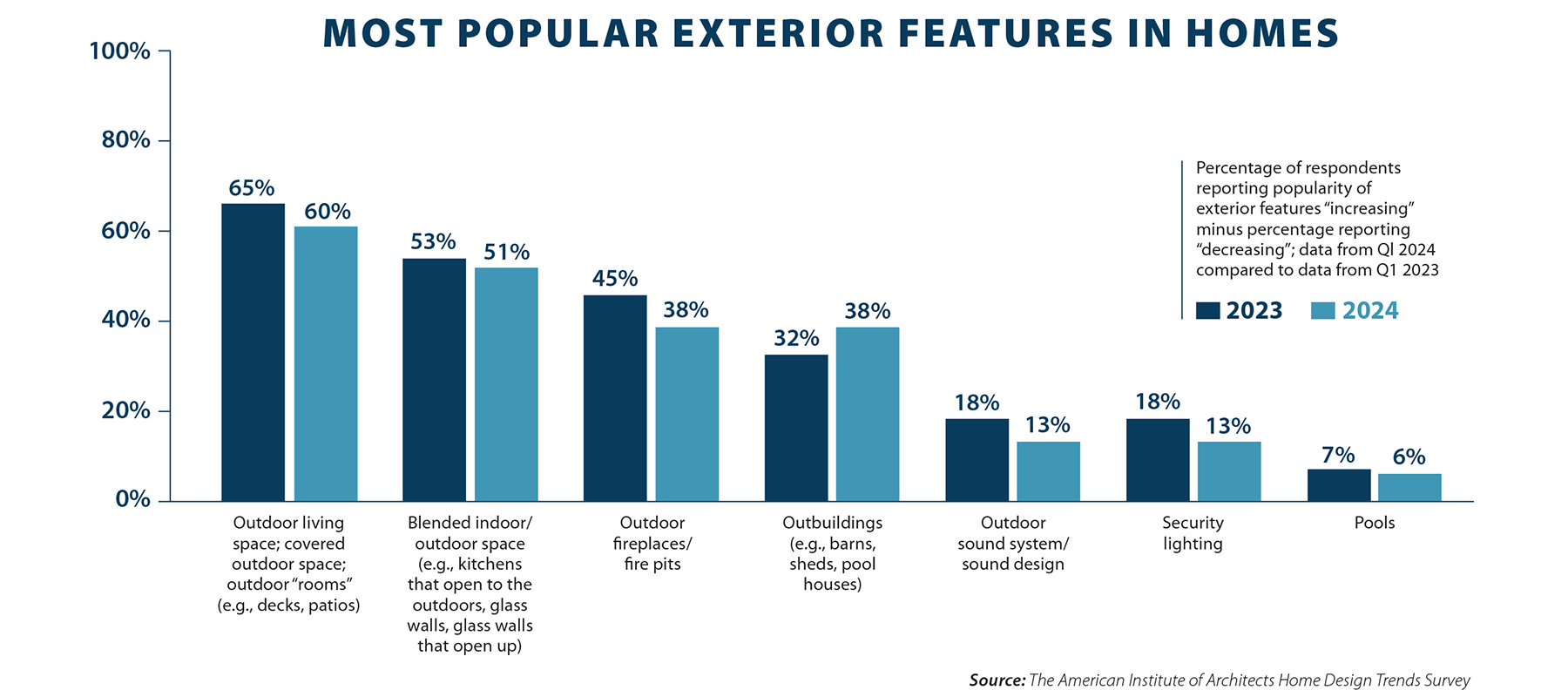

While recent data concerning the residential benefits of biophilia specifically isn’t plentiful, information supporting the idea in general is. In the 2024 American Institute of Architects Home Design Trends Survey, for example, 51 percent of architects surveyed indicated that blended indoor/outdoor living spaces, including glass walls that open up, were among homes’ most popular features. It’s safe to say that connections with nature, even if it’s simulated in a simple way within the home, can reduce stress and create a sense of calm.

That’s why Klopf prioritizes nature in the new homes and renovations his San Francisco firm, Klopf Architecture, takes on. “We can’t stress enough that nature is the main character, and architecture is meant to connect you, to provide the spaces that give you shelter when it’s needed but also a connection to nature,” he says.

Seeing Nature through Architecture

Architects use a number of strategies to harness the nurturing qualities of nature. The top strategy among them is one of the simplest, says architect Camille Jobe of Austin, Texas-based Jobe Corral Architects. “It’s seeing nature through architecture,” she says. “So you’re setting up that view — that lens — through apertures in your building.”

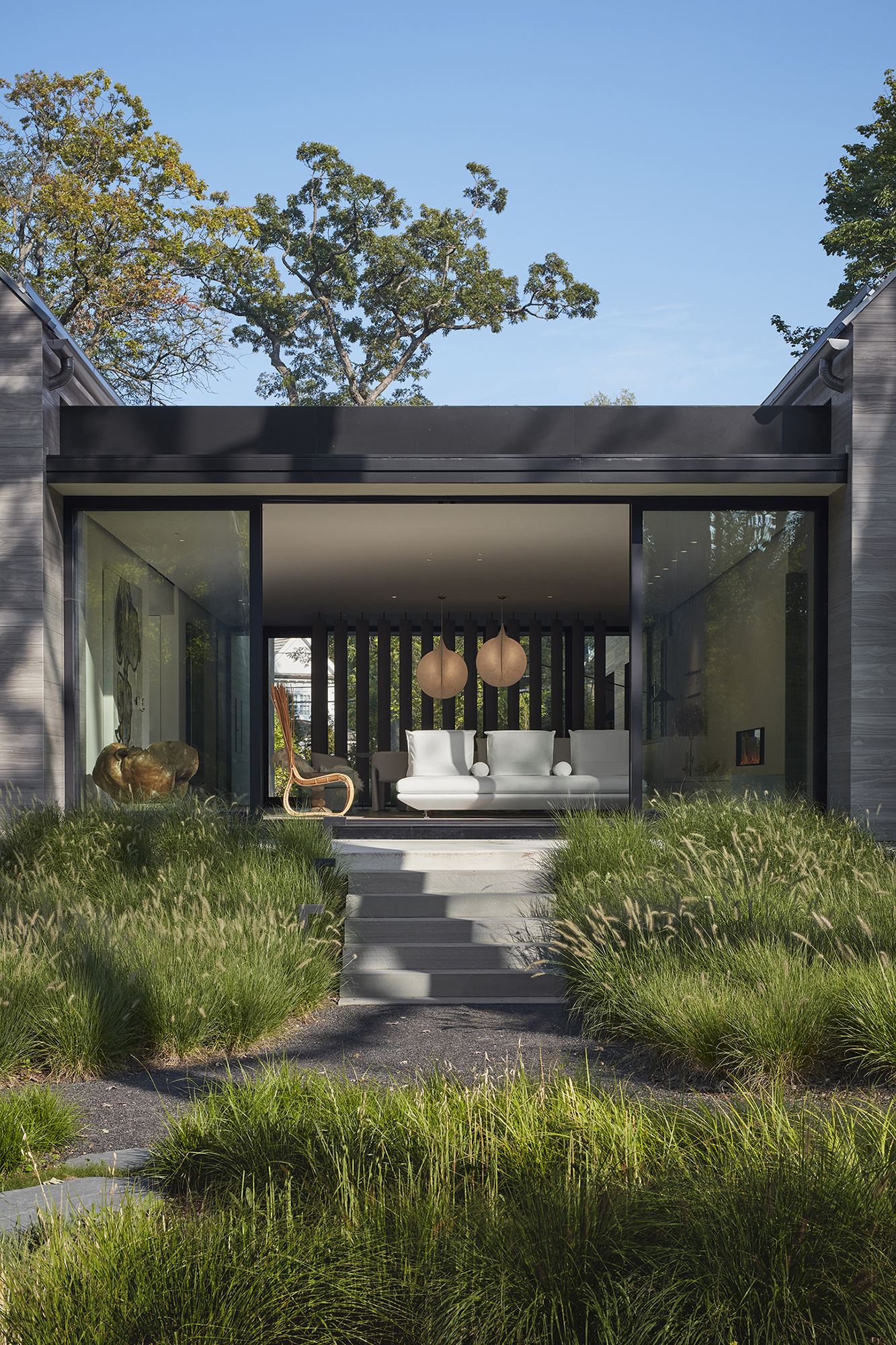

For Klopf, the idea behind that connectivity honors the midcentury-modern homes, including those developed by the iconic Joseph Eichler, that his firm specializes in. “We have studied the original drawings and the original intentions of the architecture of the time period — and I feel like we understand, through examining their body of work, what they were trying to achieve with their designs,” Klopf says. “What we have found is that they really pushed for new technologies at the time, this ability to open walls and create indoor/outdoor living spaces that bring light and views in to you.”

Among those technologies were giant pieces of plate glass, as well as sliding doors, both of which allowed for wide-angle views. “But that was the extent of the technology available during the midcentury period,” Klopf says. “Nowadays we want to push further those architects’ original intentions to open spaces as much as possible, so we use all the folding systems and multitrack sliders to push for that feeling of openness.”

He points to his firm’s Truly Open Eichler House as an example of a midcentury modern renovation that now more fully takes advantage of the principles of biophilia. On one side of the house, one-fourth of what originally could have been an entire wall of glass was taken up by a masonry fireplace. On the opposite wall, structural support posts prevented the option of installing anything beyond a simple sliding door. Removing the fireplace and devising roof support, thanks to today’s architectural technologies, opened the home to new possibilities. “Now you can open both walls completely and have nice flow to the outdoor areas from the living space,” Klopf says.

Stretching glass far and wide is something Minneapolis architect Christopher Strom of Christopher Strom Architects aims for, too. “I love any opportunity I can have to bring windows to the ceiling pane, because you allow that grazing of light and you don’t get that shadow line above the window,” he says. “When you bring that glass up past the ceiling pane just a little bit, it gives you this effect of infinite space.”

Such designs also allow interior spaces to visually “borrow” space and make smaller footprints feel more spacious, preserving as much outdoor space as possible. Nonetheless, encouraging tighter square footage can be a challenge. “I think this will always be a battle that we will have to take on as architects, because people want to maximize their space,” Jobe says. “They’re always afraid that they’re going to build this house and somehow, when it’s done, it’s not going to be enough. So, we’re always trying to have the conversation about quality, not quantity, and how you can have a small space that is right-sized. And if you borrow visual space from the outdoors and other places, it seems bigger.”

While big windows go the furthest in achieving the goal of borrowing space, sometimes the best connections to nature come in small packages. “It’s nice to have a wall with a small opening placed just perfectly for a view,” Jobe says. “One time, we had a project where the clients told us that a built-in seat we did was going to be where the dog hangs out all the time. So, we gave the dog a little window at his level over the bench so he could see if the mailman or someone else was coming. It was his little window to the world.”

A Gradual Connection

Certain climates allow for a blend of spaces from completely enclosed to partially open, to even more open, to completely open using overhanging roofs, continuations of an interior floor that become a deck or patio, and interior walls that extend out to become exterior walls, with glass doors that fold or slide to open and close off the spaces. “With all of those different elements, a person can seek out the level of connection to the outdoors that is applicable at the moment to them,” Klopf says.

His firm’s Glass Wall House demonstrates the point. A large overhanging ceiling extends beyond a wall of floor-to-ceiling glass and sliding doors from the living room to a patio living space. Beyond that patio, the space becomes more open, with no roof, before reaching a pool. “When the doors are open, from the living room, you get the fresh air and can hear the sounds of people swimming,” Klopf says. “And if you want to be a little more connected, then you move out underneath the overhang and have that opportunity.”

Jobe employs the same technique in Texas Hill Country, where the winds and sun can get strong. “You start with this very protective shell and then have these layers of exposure after that,” she says. In the deepest part of the house, thick walls provide the most protection. As you move farther out, you’re in an increasingly open space through walls of windows. And beyond that, as you go toward the exterior, you have layers of screens. In addition to the openings, architecture otherwise can gradually adjust, too. “You have this gradient of very refined, finished elements on the inside, and then, as it goes to the outside, it gets a little more natural looking,” Jobe says.

The Warmth of Natural Materials

Biophilia, not surprisingly, emphasizes the use of natural materials. Sometimes it’s stone or clay, but more often than not, it’s natural wood — for ceilings, wall finishes, cabinetry, and flooring.

The choice of materials themselves is only part of the story; placement is another. “The idea of continuing a floor material from indoors to outdoors is something that we try to push in many projects, where it’s literally the same material so that it feels like one flowing space,” Klopf says. The identical tile, for example, could stretch from inside to out, or in the case of wood flooring, the look of the flooring inside might continue outside in the form of a wood deck.

With the division between indoors and out blurred thanks to the flow of materials and minimal intrusion of window and door frames, jambs, and thresholds, light becomes part of the story, too, as it streams inside and washes the walls. “[Mexican modernist architect] Luis Barragan was a master at bringing in light and using it to create space,” Klopf says.

Strom sees the play of light similarly. “Think about the way that natural light hits that material on the outside and grazes that wall,” he says. “If it can graze right through to the inside of the house, it’s even more dynamic because it’s bringing the outside in.”

The choice of materials themselves is only part of the story; placement is another. “The idea of continuing a floor material from indoors to outdoors is something that we try to push in many projects, where it’s literally the same material so that it feels like one flowing space,” Klopf says. The identical tile, for example, could stretch from inside to out, or in the case of wood flooring, the look of the flooring inside might continue outside in the form of a wood deck.

The Origins of Biophilia

Harvard biologist Edward O. Wilson coined the term biophilia in 1984 to describe humans’ innate attraction to nature. His book, “Biophilia,” combines scientific and personal reflections about the importance of preserving the natural environment, and it remains influential in the field of architecture and design to this day. Biophilic design, which is derived from Wilson’s ideas, incorporates real or simulated elements of nature in an effort to promote well-being.

With the division between indoors and out blurred thanks to the flow of materials and minimal intrusion of window and door frames, jambs, and thresholds, light becomes part of the story, too, as it streams inside and washes the walls. “[Mexican modernist architect] Luis Barragan was a master at bringing in light and using it to create space,” Klopf says.

Strom sees the play of light similarly. “Think about the way that natural light hits that material on the outside and grazes that wall,” he says. “If it can graze right through to the inside of the house, it’s even more dynamic because it’s bringing the outside in.”

Engaging All the Senses

The sensory — sounds, smells, textures — becomes part of a biophilia strategy, too. “Whether it’s having natural materials around or just opening windows and doors and having the feeling of the breeze on your skin, all of those things are often so bleached out of our environments in buildings,” Jobe says.

“Whenever we can bring those things into play, it’s exciting. It’s what we will strive to do forever in architecture.”

Of all of the ways to bring in nature, it’s also the most elusive and ephemeral, Jobe says. “We have a tendency to focus so much on the physical and the visual that it sometimes comes to the detriment of all of those other senses.”

Key Aspects of Biophilic Design

- Views of Nature

- Natural Light and Ventilation

- Natural Materials

- Organic Forms and Patterns

She is keeping that concern in mind with a small home under construction in Carmel, California, that opens to courtyards on either side and incorporates large light wells. “You can peel the folding doors back on one side and then on the opposite side, and you can hear all of the big pine trees rustling around above you and you can smell the sea air from there,” Jobe says. “It’s very sensory.”

She has plans to put the design to the test with help from a friend and fellow architect, Chris Downey, who lost his eyesight in 2008 and continues to practice in San Francisco. “He consults with architects on this very matter, which is to quit focusing so much on what everything looks like and think more about how the spaces behave and how the rest of your senses are engaged,” Jobe says. “I have scheduled him to come walk through the house when I’m out there next for him to give us feedback on how well we’re doing with that connection.”

Designing Solutions for Every Scenario

“Bringing nature inside with help from walls of glass and door systems — even within a commercial setting — has gained momentum as an architectural goal,” says Scott Alden, Architectural Consultant at JELD-WEN. “And as we go back into offices, I think there’s some real consideration being given to making the spaces feel more at home, with softer textures and perhaps wood windows that give you more of a connection to the outside,” he says. “Historically, everyone wanted the corner office for a reason: to look out and see what was going on outside. So, there’s more of a focus on that and on health and well-being.”

Products helping architects and designers reach their goals include ever-larger windows and doors. “The trend definitely is bigger, and we’re pushing the limits on size,” Alden says. JELD-WEN, for example, can produce fixed windows up to 72 square feet — measuring 7 feet wide and 10 feet tall for floor-to-ceiling installations, for example — as well as sliding door panels nearly as large.

Large-format options up to 12 feet tall and 24 feet wide take full advantage of scenic views and make indoor and outdoor living virtually indistinguishable. The patio door structure and the way the system functions also contribute to seamless indoor and outdoor spaces. “Our patio doors today include slim frames with more glass, plus additional options like flush sills and recessed hardware that create bigger and cleaner openings,” Holland McGraw, JELD-WEN Product Marketing Manager for Windows & Patio Doors, notes.

Energy efficiency and protection from the elements factor into window and door design. “You’re looking for water resistance, wind resistance, and energy efficiency — things that a window provides from a performance perspective — but the fenestration is something you are looking through, instead of at,” Alden says.

Wood windows with natural finishes fit biophilic aesthetics particularly well. So do windows with paint that still shows off the beauty of the wood’s grain, as well as a wide array of semi-transparent stain colors.

When selecting wood windows and patio doors, consider weather-protection innovations that help them stand up to the elements. Among JELD-WEN’s product options is AuraLast® pine, (link to ) which provides protection

against rot, water damage, and termites. The patented treatment process fortifies wood all the way to the core, providing superior protection from the elements. The water-based treatment adds no color or odor to the wood, and the manufacturing process releases 96 percent fewer volatile organic compounds (VOCs) than traditional solvent-based methods. “We have designers who choose to use a clear coat finish on pine, and it’s beautiful,” Alden says.

Large windows and doors from JELD-WEN and LaCantina can help architects, designers, and builders meet their biophilic design and construction goals. Both manufacturers offer window and/or door designs, colors, and materials rooted in nature, as well.

Comments are closed.